More from Our ‘Most-Read Authors’ Report (and Why Bylines Matter)

The response to our report last week on the “most-read authors” in Read It Later was incredible. One thing is clear: We can learn a lot about the value of great content, outstanding writing and what resonates with people by paying close attention to who’s creating it, and how readers are consuming it. We’re now at 4 million readers and viewers—the largest time-shifting platform on the web—and we feel a responsibility to show how content accessibility can change the way we enjoy what’s out there.

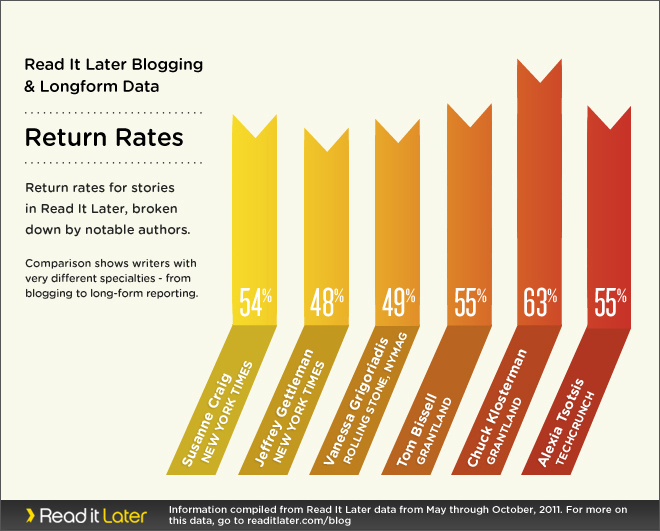

Some notes from last week’s coverage: The New York Times’ David Carr and others reported on our “most-saved” authors, as well as the new concept of “return rates.” That is: It’s not just which authors our users saved, but which authors they returned to. That can say a lot about loyalty to a byline, and the longevity of what they create.

Most-Read Authors: Not the Same as Most-Read Publishers

It’s important to add that our data reflected only the most-saved and ‘most-read’ authors—not the most-saved publishers. As you’ll see soon, Read It Later’s most-saved publisher list is quite different than who ranked highest on our author lists. For example: While Lifehacker’s individual authors were top-ranked on our most-saved authors list, The New York Times is five times more popular overall as a publisher.

One reason has a lot to do with the sizes of various publications’ editorial staffs. The New York Times has hundreds of writers, so their engagement is spread across many different bylines.

Gawker Media properties all did extremely well in the most-read authors report, and there were some fascinating examinations of why Lifehacker ranked atop the “most-saved authors” list, while Deadspin ranked at the top for “highest author return rate.” But why did Gawker Media do so well? Again, look at the Gawker Media mastheads. Small staffs, high volume of traffic.

The Power of ‘Return Rates’—and the Writer’s Voice

The New York Observer’s Foster Kamer also noted some interesting similarities among the writers with the highest return rates—they all have strong, very distinct voices, which suggests a loyalty to the individual writer that we’ve always guessed was true, but could never quite quantify.

Kamer also had a very funny take suggesting all those Lifehacker people saving their to-do lists were not actually getting around to crossing anything off their lists. But actually, most Lifehacker authors had above-average return rates. So maybe our users are pretty productive, after all.

Finally, Nieman Lab’s Megan Garber had a sharp take on what engagement looks like in a time-shifted world, and we think this underscores what’s so interesting and important about “Return Rates” as a way to judge depth, longevity and loyalty to an author, publisher or topic. Many of our highest-return rate authors came from the category of sports, TV, and politics. But there’s a lot more to explore in terms of how those categories resonate in terms of reader loyalty.

More than anything, we hoped last week’s report would start a whole new conversation about how we measure the quality of what’s on the web: After all, it’s the content, created by writers, editors, producers and publishers, that make people so passionate about time-shifting.

Through transparency we at Read It Later hope to give them more insight into how their work is enjoyed. We will continue to share what we know with our users.